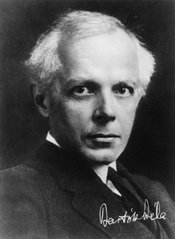

(1881-1945)

Béla Bartók was a composer, researcher of folk music, pianist and teacher. While still a young child, he demonstrated perfect pitch at the piano lessons he received from his mother. By the age of seven, he was writing piano pieces. Later on, he continued his piano studies at the high school in Nagyvárad (Oradea), often appearing at the school's ceremonial events as a pianist and composer and playing the organ in the school chapel until graduation. In 1899, he enrolled at the Ferenc Liszt Academy of Budapest to study piano and music composition. His first successful Budapest appearance came in 1901, when he was heralded as the sole worthy successor to Dohnányi. While his composing stalled during this period, he was gaining a familiarity with the musical world of the capital bourgeois salons as well as making progress with his music history studies. In the summer of 1902, he resumed composing and with the large-scale works he completed the following year had already made the first steps toward realising what from this time on would be his life's ambition: to create a form of art music combining the most modern European techniques with indigenous Hungarian traditions of such a high order that it would simultaneously contain both elements of musical cultural criticism and a humanistic and national programme that transcended criticism. After completing his studies, he performed concerts abroad. However, despite receiving critical acclaim, he was unable to break into European concert life. In 1907, he joined the faculty of the Liszt Academy. Together with Zoltán Kodály, he also delved into researching folk music on an extensive scale. On his tour of Székely Land, he set out on the trail of the ancient Hungarian pentatonic melodic style. He also collected the music of other peoples with the aim of discerning what it was that made Hungary's folk music unique. The influence of non-Hungarian folk music started to appear in his music from 1908, and it was partly through these that he moved beyond his originally narrower objectives. With his ever more intense arrangements of peasant music, he developed his mature musical style, as well as the most important dominant poetic theme of his stage works: the conflict between man and woman. His music from 1908 onwards belonged to the most significant and most personal achievements of the new European art. At the same time, the individualistic, dissonant and modern sound of crisis in his music was collectively and passionately rejected by a large segment of music critics and the wider audience both in Budapest and abroad. In 1911, together with a few Hungarian composers and performers, he founded the New Hungarian Music Society with the intent of reforming Hungarian musical life, but public indifference and the lack of official support doomed this initiative to founder. In despair over the rejection of his opera, he retired from performing concerts. From 1921, the situation changed again: his schedule was packed with concerts to play in Budapest as suddenly growing international recognition enhanced his prestige. Over the course of ten years, he made 271 appearances in 17 countries on two continents. His pantomime-ballet The Miraculous Mandarin was rejected in Hungary, and so the premiere took place in Cologne. Starting in 1931, he would only compose music by commission. He quit teaching in 1934, becoming a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, where he documented and organised his collection of folk music. In 1937 and 1938, he collaborated on directing the musical component of the large-scale ethnographic recording series launched on Hungarian Radio. Opposed to the fascist regime, he emigrated in 1940 to the United States, where he continued his research into folk music and accepted an honorary doctorate from Columbia University. He died in New York. The greatest figure in Hungarian music history and one of the greatest in Hungarian civilisation as a whole, he embodied one of his country's most significant contributions to world culture.

Béla Bartók was a composer, researcher of folk music, pianist and teacher. While still a young child, he demonstrated perfect pitch at the piano lessons he received from his mother. By the age of seven, he was writing piano pieces. Later on, he continued his piano studies at the high school in Nagyvárad (Oradea), often appearing at the school's ceremonial events as a pianist and composer and playing the organ in the school chapel until graduation. In 1899, he enrolled at the Ferenc Liszt Academy of Budapest to study piano and music composition. His first successful Budapest appearance came in 1901, when he was heralded as the sole worthy successor to Dohnányi. While his composing stalled during this period, he was gaining a familiarity with the musical world of the capital bourgeois salons as well as making progress with his music history studies. In the summer of 1902, he resumed composing and with the large-scale works he completed the following year had already made the first steps toward realising what from this time on would be his life's ambition: to create a form of art music combining the most modern European techniques with indigenous Hungarian traditions of such a high order that it would simultaneously contain both elements of musical cultural criticism and a humanistic and national programme that transcended criticism. After completing his studies, he performed concerts abroad. However, despite receiving critical acclaim, he was unable to break into European concert life. In 1907, he joined the faculty of the Liszt Academy. Together with Zoltán Kodály, he also delved into researching folk music on an extensive scale. On his tour of Székely Land, he set out on the trail of the ancient Hungarian pentatonic melodic style. He also collected the music of other peoples with the aim of discerning what it was that made Hungary's folk music unique. The influence of non-Hungarian folk music started to appear in his music from 1908, and it was partly through these that he moved beyond his originally narrower objectives. With his ever more intense arrangements of peasant music, he developed his mature musical style, as well as the most important dominant poetic theme of his stage works: the conflict between man and woman. His music from 1908 onwards belonged to the most significant and most personal achievements of the new European art. At the same time, the individualistic, dissonant and modern sound of crisis in his music was collectively and passionately rejected by a large segment of music critics and the wider audience both in Budapest and abroad. In 1911, together with a few Hungarian composers and performers, he founded the New Hungarian Music Society with the intent of reforming Hungarian musical life, but public indifference and the lack of official support doomed this initiative to founder. In despair over the rejection of his opera, he retired from performing concerts. From 1921, the situation changed again: his schedule was packed with concerts to play in Budapest as suddenly growing international recognition enhanced his prestige. Over the course of ten years, he made 271 appearances in 17 countries on two continents. His pantomime-ballet The Miraculous Mandarin was rejected in Hungary, and so the premiere took place in Cologne. Starting in 1931, he would only compose music by commission. He quit teaching in 1934, becoming a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, where he documented and organised his collection of folk music. In 1937 and 1938, he collaborated on directing the musical component of the large-scale ethnographic recording series launched on Hungarian Radio. Opposed to the fascist regime, he emigrated in 1940 to the United States, where he continued his research into folk music and accepted an honorary doctorate from Columbia University. He died in New York. The greatest figure in Hungarian music history and one of the greatest in Hungarian civilisation as a whole, he embodied one of his country's most significant contributions to world culture.